The History of Taylor Communications A tradition of innovation in business and the community

Founded on the vision of John Q. Sherman in 1912, Taylor Communications stands out among a distinguished list of dependable, innovative and growing companies established and still operating in the Dayton, Ohio area.

Shortly after Dayton, Ohio’s Wright brothers gave the world wings, Standard Register introduced Daytonian Theodore Schirmer’s paper-feeding invention, the pinfeed autographic register. This revolutionary device simplified business transactions and became the "standard."

Taylor Communications has since evolved to offer a variety of products and services aimed at simplifying business processes with information solutions.

The Seeds of Taylor Communications

The Seeds of Taylor Communications

Just a few years after the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight in 1903, another Dayton, Ohio, inventor, named Theodore Schirmer, introduced a new principle of feeding continuous forms through an autographic register. He knew that continuous forms could not be fed accurately by means of friction rollers.

Schirmer had observed the operation of the chain and sprocket gear that often replaces belts and pulleys where absolute positive drive is required...a principle later adopted by other industrial fields such as motion picture film, monotype casting strips, etc. It became obvious if holes could be punched along both margins of a strip of continuous forms to engage sprocket wheels with pins, positive feed would be possible.

He conceived a register with a wooden cylinder built in the head with a roll of small studs or pins encircling the cylinder near each end arranged to engage the holes punched in the paper. The idea appeared practical and he obtained a patent.

Schirmer then turned his thoughts toward marketing it. To obtain funds, he made repeated attempts to interest individuals with financial resources. While some openly laughed at the idea, others thought it was good, but of questionable commercial possibilities in a field where competition was already established. Apparently the new idea was doomed to oblivion where many ideas have gone for want of effective promotion.

John Q. Sherman came to Dayton from Excello, Ohio, to "seek his fortune." He worked as a molder and studied at night. In Dayton he opened a small real estate office, and expanded into the field of buying and selling businesses of various kinds on a brokerage basis, from time to time running advertisements in the local papers.

John Q. Sherman came to Dayton from Excello, Ohio, to "seek his fortune." He worked as a molder and studied at night. In Dayton he opened a small real estate office, and expanded into the field of buying and selling businesses of various kinds on a brokerage basis, from time to time running advertisements in the local papers.

Schirmer replied to one of Sherman's newspaper ads, hoping that Sherman advanced money on businesses as well as buying and selling them for others. At first, Sherman dismissed the whole thing as being entirely out of his line. But the more questions he asked and the more knowledge Sherman gained of the autographic register industry and its problem of form feeding, the more his interest increased in the possibilities of Schirmer's invention.

Finally, he asked Schirmer to construct a working model of his invention with sufficient punched paper to provide a thorough test. With access to this model, Sherman quickly saw improvements and refinements that should be made.

The register had only one moving part, doing away with the rollers, springs, gears and ratchets necessary to the operation of ordinary registers. This meant that instead of just two or three copies, as many as eight copies could be made at one writing with all copies positively fed through the register. It meant that all copies could be printed with lines, check blocks, imprinted items and other things so that forms could now be designed for many systems in addition to the simple sales slip.

The autographic register could now be applied to bills of lading, express receipts, purchase orders and thousands of other applications for which the friction-feed registers were impractical.

Beginning the Corporation

Finally, Sherman's enthusiasm reached the point of action. Without adequate funds of his own, he solicited a few investors and conveyed to them his vision of the possibilities of the new idea. A limited amount of capital was obtained with great difficulty, and on May 11, 1912, John Q. Sherman and four others obtained a charter for The Taylor Communications Company with Theodore Schirmer as President and Sherman a member of the Board of Directors.

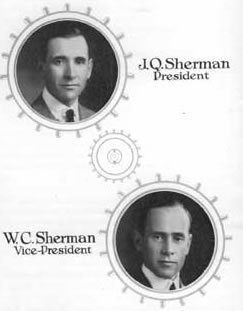

J.Q. Sherman sold his real estate business and became active in the new enterprise as it began production. With the business organized, Sherman left management to his associates and went to the Pacific Coast to operate one of the first sales agencies for the new register and punched forms, leaving his brother, William C., to represent his interests.

The Dayton flood in 1913 caused the fledging company to miss many delivery dates, and order cancellations or threatened cancellations pushed the firm toward financial disaster.

Within a few months, an announcement was made that a receiver for the firm was to be appointed. W.C. Sherman called his brother back from the west coast and they canvassed the investors. Explaining the situation, scraping together every available cent of their own, including borrowing on their life insurance policies, they bought out the majority interests and took active charge of the management of the business.

Within a few months, an announcement was made that a receiver for the firm was to be appointed. W.C. Sherman called his brother back from the west coast and they canvassed the investors. Explaining the situation, scraping together every available cent of their own, including borrowing on their life insurance policies, they bought out the majority interests and took active charge of the management of the business.

The reorganization of Taylor Communications left J.Q. Sherman as President and W. C. Sherman as Vice President and Treasurer.

The first problem which confronted the new management was to increase production and turn out accumulated and long overdue orders. Since the three small presses were already running at capacity, and no capital was available to purchase new equipment, the only solution was to operate the presses at night.

Unfortunately, the building that housed the small company shut off the central power plant at 6 p.m. every night, so no power was available for running the presses after that hour. W.C. Sherman packed a bag with the company's unfulfilled orders and current operating statement and solicited local banks for a loan to purchase an electric motor to continue operating the presses.

Two of Dayton's leading banks turned him down; but on his third attempt, the loan was obtained, the motor purchased, production doubled, and within seven months the receivership was removed.

In 1917, a one-story, modern factory was built at the present location of Taylor Communication’s headquarters in Dayton. These new production facilities were quickly outgrown, and the first of a series of factory additions was built. From then on, even through the depression years, it was a race to provide production facilities to keep pace with sales.

J.Q. Sherman had closely watched the development of business machines for machine-written records. He noted that one factor impeding the full utilization of the speed of these machines and the skill of the operators was the inability to feed continuous business forms with the almost universally used cylindrical friction feeding method. He reasoned that the "pinfeed" principle could and would solve the problem.

The development of the REGISTRATOR Platen made it possible to feed marginally punched forms through typing machines with precision and minimum handling costs. Manufacturers of business machines were among the first to appreciate the revolutionary character of this invention.

No sooner had the announcement been made than several leading manufacturers approached Sherman in an effort to secure exclusive rights to the use of the REGISTRATOR Platen. J.Q. Sherman decided to give his invention the broadest possible use, permitting users of all types of machines to enjoy its benefits.

A Leader, Taylor Communications, Emerges

In 1933, the Shermans invited Milferd A. Spayd and other experienced executives to join the company. A five-year planned expansion program was implemented and the company grew rapidly.

Sales volume increased from $1 million annually in 1920 to $5 million annually in 1940. At that time a new plant was built at the Dayton location. Taylor Communications built a carbon plant to insure providing the highest quality product possible to its customers.

The outbreak of World War II brought government restrictions and business forms were declared nonessential. But General Motors President, Charles E. Wilson realized that "no physical activity goes on in our modern age without a piece of paper moving along to guide it."

Paperwork was found to be important to the war effort because it controlled munitions manufacturing, tank building operations, material procurement, troop movement and many other things. Marginally punched forms and other equipment for speedy processing of information were needed by defense plants, shipyards, and the services themselves to keep men and materials moving.

The government finally recognized business forms production was an essential business, and, by the end of the war, Taylor Communications had been given one citation after another for its contribution to the war effort.

During the war years, both of the Sherman brothers died, and M.A. Spayd became President of Taylor Communications in 1944. During the war a group of industrial engineers had developed a technique they called Work Simplification. Essentially it was a formula by which any production worker could arrive at improvements on his own job or show others how to improve their jobs.

Remarkable results were reported. The company transferred this job improvement formula from the factory to the office and used it as an organized approach to the improvement of a procedure or system.

It was called Paperwork Simplification, which eventually was referred to as Process Improvement: A Working Procedure taught to sales representatives and a staff of systems consultants.

This technique was widely in demand during the war and Taylor Communications continues to help customers improve their business processes to this day.

The company was broadly recognized for its continuous improvement and forms management programs. Customers purchased marginally punched forms and document handling devices, but, they also received process improvement services. Apart from the original invention of the pinwheel and the origination of marginally punched forms, process improvement is the most important contribution Standard Register has made to American business.